Sunday, August 13th

I left. New York and the job. I haven’t told them yet, hoping lunatically that they become as angry and confused as I have been. The price of their unconcern will be the opposite in the extreme. It might even be good publicity, for someone.

There’s so much I missed in trying to miss nothing. Too many of my experiences just blurred observations, like the way one sees close-hemming trees on a fast road. With today alone as evidence, I am doing the job closer to what I, and perhaps they too, imagined. But I am not in Connecticut. I’m in Pennsylvania, just across the Delaware River and over a bridge that separates it from New Jersey, in a town called Rieglesville. I’m sitting at the bar of the Rieglesville Inn. Their kitchen is closed, so I’m having a Miller Lite at the bar, wondering what it is I should be writing.

Whatever came in those three or four weeks before now, I won’t say. Won’t dare glance at the echo of the disappointing unseen and unheard and unmet. It is gone, was gone when I passed through like ungrateful lightning.

More could be said about it. Hell is parallel to heaven, and I was on the wrong rail. I’ve shed obligations like a raccoon that’s released his grasp of the silver coin inside the glass jug. Money and stature. I’ve slit their throats like goats, regretfully. But I still dragged the blade across the flesh, felt the scratch of the hair against the edge. Anyway, bad writing imminent — I will just do what I have always wanted.

This morning, still in New York, I was angry, furious. I had to walk out of yoga. I was unready for chakra work, unwilling to accept the glossed lesson and enter its logic. I walked out once the chanting portion had stopped. K understood. So did L . I smoked and called Susanna; I gave myself over to that anger for once and clarity resulted. I held onto the feeling of the pull to get out and go west instead of northeast, letting the after-thoughts whither on the neurological vine.

After a cigarette with Luis, I went back into the studio for the meditation, during which I recalled my ‘teacher’ from the session the week before when I had wept—an older version of myself. L asked how it had gone for me, remembered what I had said, and understood that it had gone well for me. K said she also focused on self-assuredness—I didn’t tell her that the kind I wanted was, additionally, in spite of uncertainty.

We ate at a kosher restaurant. I had a smoked whitefish sandwich with a bright green pickle, a glass of carrot juice and a small bowl of cold borscht. K had a sandwich with mozzarella and L had eggs and potatoes. We walked a bit more, talked some. I hugged them. They wished me luck. They were the first people to say that my plan to blow things up sounded like a good one.

Leaving New York was slow, jammed. New Jersey was the worst part. I bought gas there—I forgot they fill it up for you—for $1.20 less than what it cost in Manhattan ($4.90). I bought a scratch off to justify cutting through another gas station to avoid a one-way in the wrong direction. I thought I won $20, having revealed, on the crossword, the words “nut,” “kin,” “fossil” and one other I can’t remember. I hadn’t read the fine print, and displaying my disbelief to the cashier, left laughing at what I still believed was my terrible luck.

America starts where they grow corn. The road narrows, becomes less potholed and pockmarked, smoother, cooler, bluer. I got further into a part of a state the parts of which I had never considered. West New Jersey.

The road became just two lanes loping and heaving and wandering through hills. The towns became old stone, alabaster and cream and grave. The houses became taller and wider but thin, two stories with shutters, American flags furling and unfurling in the breeze, reclaimed barns, many still red, and some still paired with their siloes like lovers grown old. More corn. Dusk, and the ears scaled with shadow and blown apart by golden setting sun and neon, translucent skin over throbbing green blood.

I stopped to take photos. A stone house, a barn, a silo. I saw a hot air balloon in the distance, and when I stopped by a cornfield to take a photograph, I saw another just beginning to rise over a low ridge beyond—a view.

There was a town called Twp of Greenwich. More stone houses. Unbelievable. Hidden from all the world, the rest of the country included. Wide slat colonials, too. And, after passing through the narrow arch of a bridge, my eyes shot awake to the glinting of a river, speckles of white-blue past young tree trunks. A turn out. No fast cars behind or cross traffic. I slid in to park.

I heard it. Trickle and wash and the thousand spaces between each warping swirl and combusting gurgle, a raucous whisper that only a small river, one that is often-times only a creek or stream, can make. Erect between the ears, I grabbed my towel and smiled down the muddy track to its bank, ignoring the louder rush at the end of a muddier footpath, finding a rough-hewn wood bench, built for those who know by others who knew.

Stripped of the non-essentials, I wobbled in over the larger, side-strewn rocks, past a bit of soft current to the wading friendly midriff speckled with smaller rounder stones nearly all good for skipping. It was shallower there and bookended by foot-and-a-half deep channels perfect for laying and bobbing, for flippering ones hands and gliding downstream.

I swam in place a few moments, glad for the exercise and climbed out, viewing the magical isolation of the place. The Musconetcong, a trout river and a good omen.

Driving on, I came to an old steel, blue-green bridge and crossed it. The road after, a street to those living there, diverged ninety degrees, and I parked at the Riegelsville Inn.

The kitchen was closed, so I sat at the bar for three Millers and wrote as the wait staff performed closing duties and delt free drinks. Over a cigarette, one of them asked my name. His was Brad. “Where the hell am I,” I asked to laughter. “I’ve been asking myself that same question,” he clichéd, and not much more came of the conversation, a ‘fuck ‘em,’ offered as luck.

Brad said I’d be fine to park my car across the street and held the door open for me when we both went back inside. I finished my beer and this part of the story.

Monday, August 14th

(See notes for morning)

There are no notes. There no longer are any notes. Thinking I’d finished this, I deleted them — maybe that’s why Graywolf didn’t accept the pitch, though I doubt it. I’ll just have to supply my best recollection here, in italics.

I woke that morning after a deep sleep and a long phone call with a friend who was, unknown to me, becoming increasingly mentally ill. The soothing rush of the river and the coolness of the air laid over it had done much to ease my worries. The sun was still rising above the trees, and only a few cars passed over the bridge as I made the bed and heated water for a cup of instant coffee. I took it with the dark honey I’d bought back somewhere that had such things and smoked my first cigarette, pacing up and down the green strip of high bank between the van and the bridge, hoping the day would provide a sign.

There wasn’t much of a town to stroll through, and the second right angle turn away from the water proved nothing existed that would be open for breakfast. I crossed the footbridge that straddled the long river overflow ditch that formed the back border of the hotel’s property. There was a single running jogging up the wide path next to it, and I waited for her to pass before I shuffled down and pissed in the overgrowth.

Only the Reigelsville Roebling Bridge monitor had been alive and awake before this, and I periodically looked his way, and he mine; and though I could not discern his expression, it was my first experience of that look locals give loitering out-of-towners, the confusion and suspicion of which can be entirely felt by the person observed.

I was finishing my coffee when I got close enough to the landmark sign denoting the bridge’s name and date of construction. Opened for traffic April 18th, 1904. I had been looking for signs; my birth date, a hundred and twenty years in the past would suffice. I got my phone from the van and went back over to take a picture of the sign, securing the proof of some god’s existence, at least for the last hundred years or so.

A last cigarette over the Delaware’s slow morning creep, and I packed up the stove, rinsed my coffee mug and drove on.

I made my way slowly. Recalling the day now twelve hours past is difficult. I am already grieving the job, what it could have been, anyway, and fearing the uncertainty ahead.

The plan was to buy a fly rod and get to my campsite, where I expected to do some fishing. I accomplished both, but in the opposite order. The drive was slow. More corn, more siloes, dairy cows now. The names of the towns turned from English to German for a stretch before turning back into English. All of them materialized from behind slow, sharp bends in two-lane, well-kept roads—old stone and clapboard two-stories, some grey with time, huddled against the shoulders as if to keep warm from the asphalt or to insist on their remembrance.

I finished an entire roll of Kodak Portra 400, though I could say less of what was on tho film than what remained lost to it. Barns, siloes, houses, a decayed diner, some hay maybe. As the looking for and taking of pictures revealed, the people became suspicious here; this is the border between effluescent American flags and the fewer, more insistent other kinds—Come and Take ‘Em’s fielded quixotically by Confederate stars and bars, some Don’t tread on me’s, a pot leaf.

When I stopped to take a photo of a red, rust-pitted truck parked forever against a barn of the same color, a young man waved me down. I waited. He waved again, meaning my window. “Can I help you with something,” he nearly asked. I explained I was just taking pictures. “Well, it’s just this is my dad’s property,” he nearly apologized. “But there’s a building about a mile down the road that way that’s made entirely of brick.” I lied that I had seen it and thanked him.

Another home owner became observably curious when I stopped out front to photograph his house. He was mowing the grass. So many rural Pennsylvania homes look unoccupied. They are not.

I got to Allentown, skirting its sides to avoid what I assumed to be an unimpressive middle, stopping only to photograph three geese near a public pool fallen into disuse. I kept going.

Past one of those thousands of miniscule downtowns—experiments that only began with plenty of hope—I found a Dutch country store. Dietrich’s advertised a “PA Dutch Music CD by Local Artists: 80 Minutes of Music $15.” I went in and asked if they could make a sandwich. “We don’t have lettuce and tomato, but we can do cheese, mayo, mustard.” I sampled the liverwurst and asked for spicy mustard. They had plenty of local goods—honeycomb, homemade Dutch pasta, pickles, sauerkraut, all kinds of sausages, lambs tongues—but I only took a picture of the whole, smoked pig’s head that you could buy for your “hund.”

Turning off the Old Highway 22 onto a unnamed, gravel road, I looked for a scenic place to eat my lunch. I didn’t find one. The shoulders are far too narrow or soft in these parts, and turn-offs too rare and sudden. I startled what I thought was a marmot and what I knew was a barn cat which turned and waited to get a look at me.

Tindel is where I stopped to eat, parked on the street across from a Chinese restaurant that was rivaling the rest of the town’s historic buildings for most aged in appearance. I got out and walked around but was less impressed than I expected to be. An old movie theater showing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, a First Reformed church with stained-glass windows that reminded me of the ones at the church I grew up going to, and two signs that promised “Vape shop coming soon.” I heard two young women talk about an upcoming wedding and an approaching birthday, and I knew what people did around here.

I called my mother and started driving out of town. She was as reassuring as she could be. I’d received texts from both that I’d ignored. But at least the job I still had responded with some understanding. I felt better that at the end of this road, I wouldn’t be broke, but I hadn’t yet checked my bank account.

I passed through Hershey, the details of which were in the same deleted notes as those belonging to the morning. The town made an impression, but not one that surprised or was worth dwelling upon. I drove around the outer rim of the park, noticing areas of poorly kept fencing that might allow a free entrance to the eager and resourceful. I didn’t have time to stop, nor did I want to make any. The houses got larger and more impressive as I got across town, the colonial sort that evoked a continuous gentile line. Confederate flags melted into chocolate signage which gave way to red, white and blue once more.

There is a Bass Pro Shop outside Harrisburg, which is a lot like Allentown in that it happens quickly or not at all—except for the people who live there for whom they happen all the time, perhaps painfully so. By then, towns had ceased creeping so close to the road and the structures became wide, commercial and franchised. This is where you find the Bass Pro.

The man who helped me inside was fat, white-mustached and helpful in that pleasantly light manner novices appreciate. I chose a 7’6” 3-weight rod for $159 that came with its reel already wound with line and a leader and included a tube as well as a 10-pack of assorted caddis flies for $20 and a 5-in-1 toolkit for another thirty. It came to $225 with tax.

I was near a river already, the Yellow Breeches Creek, and I wound out of my way around its sides looking for a break in the unforgiving shoulder. I found one, set up and started casting, losing my first fly immediately—a bad knot. The second one lasted all day, but in this first spot I was too anxious that a neighbor might rat me out for not having a permit, which they couldn’t have known but might have had the gall to find out.

I drove to Boiling Spring—no eastern American town is not historic—where a fishing blog had noted popular spots to catch the Yellow Breeches’ year-round trout. I passed through the town where there was a fly fishing store—I had wanted to buy local and now knew I could have. But the spot mentioned was back out of this town at the Allenberry Resort, an upper-middle class-fancy getaway with ‘lodges.’ I parked in the gravel lot below Meadow Lodge, also mentioned.

The Yellow Breeches, here, was beautiful and well-maintained with large cut stones lining it in parts. There was a young couple already fishing what appeared to be the best part, though not with flies. I worked around them, trying a few locations, but I mostly practiced my cast. A single fish might have precluded the doubts growing out of my weariness.

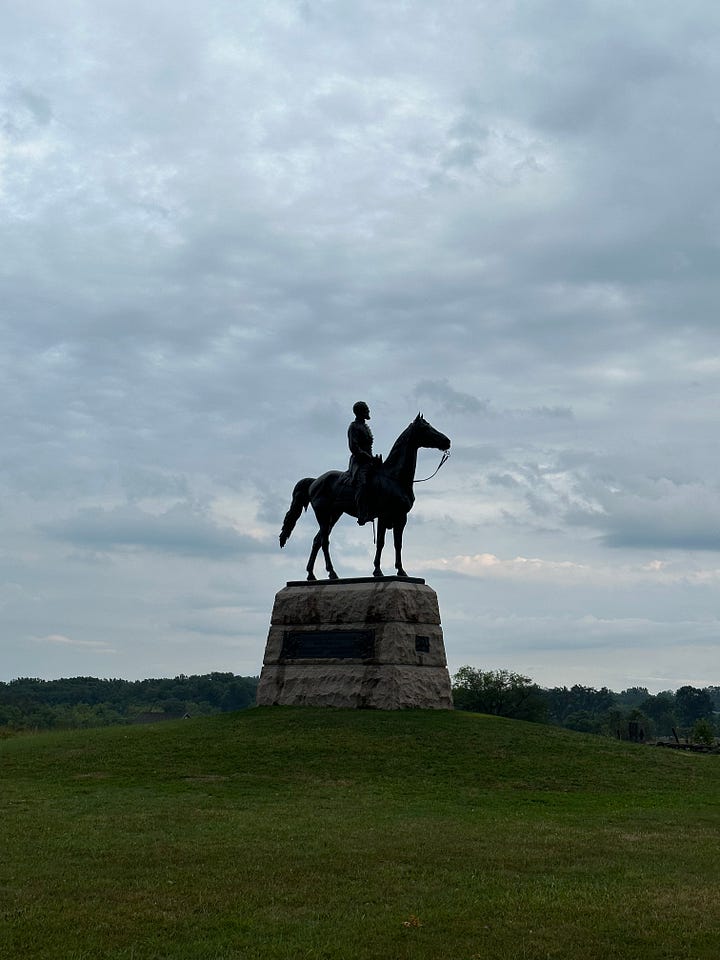

Gettysburg came next. I almost didn’t stop, having already made an out-of-the-way pass through Hershey. I parked at Cemetery Hill and called S . I needed to feel her near me, even though my thoughts were failing to form around my newest feelings. I saw two rabbits and read the Union regiment monument markers, the number of casualties—fewer than I expected, until I reached the flank at the Bryan House. Of course, strategy.

I drove around the downtown filled with souvenir shops and themed stores—Civil War era woodworking and the like—before stopping at the McDonald’s visible from the battleground and ordered two McDoubles, a medium fry, a coke and bottle of water. They gave me an extra kids sized coke; I was still on the phone with Susanna and giggled.

It was starting to get dark and it rained lightly, excusing me from making more stops to take pictures or get a better glimpse of any small towns, and I arrived at Cunningham Falls State Park five minutes before the camp store was due to close. I bought a bundle of firewood and checked my bank account—$452.88. Two thousand less than I’d expected; a few large payments made over the weekend had not processed on time.

My anxiety welled up when another concerned text came through. I messaged Susanna; she told me not to worry, to trust my decision. I thought $450 is awfully close to what William Least-Heat Moon had had when he started Blue Highways, and I’m only driving across the country not around it. Still, it would be a challenge. To avoid dipping into the tax money already set aside, I’d have to catch my dinner some nights and certainly avoid camping fees.