There wasn’t much noise where I was in Louisville—a few partiers in cars with loud engines playing loud music, but not late. I got caught up looking at apartments in Richmond and sending Susanna my results and she hers to me, and I didn’t go to bed until nearly two, waking up at 10:30.

I walked the block and half to a coffee shop, ordered an iced coffee and a bacon egg and cheese biscuit to go before taking a shit in the bathroom and hearing them call my name three times before relenting.

The conversations in the cafe confirmed to me that Louisville was not a place I wanted to stay for long, let alone live. Southern-city liberalism, and its tendency toward making everyone a soft pedant, was here whether or not the place felt large enough to call a city.

I drove further from the center of town to a photography shop called Murphy’s, passing a record shop with which I’d become familiar at a distance only a couple months prior while on the job I’d since left.

The older, nearly white-haired man at Murphy’s was helpful. I decided not to have my five exposed rolls developed and bought a lens cap, a battery for my point-and-shoot that ended up being the wrong size, two rolls of Ilford HP5 and a five-pack of Portra 400 for $121.91: a write-off. I told the man about my trip when he asked where I was from, and he wished me luck and good photos on my journey. A younger black man asked what I was shooting with, and I showed him my camera and said “HP5 and any color I can get my hands on,” as we both smiled and I loped out.

Down the block, the record shop wasn’t open yet, so I parked across the street, ate my biscuit and got out to smoke a cigarette in the cooler heat of the open air.

Once Surface Noise had opened, I did what I’d come to make a habit of in places like this and looked for the magazine, a seance for a recent ghost of an already distant past. I didn’t find it. From the clerk’s appearance, and some of the more progressive media on display, I assumed why.

On a small bookshelf in the back, I took notice of only one book, a play by Tennessee Williams called “Summer and Smoke.” Intrigued by the title, and further by the summary on the back cover which reminded me of Susanna, I decided to buy it. I paid, chatted with the clerk, mentioned who I was and by whom I’d been previously employed and left a brief note for the owner.

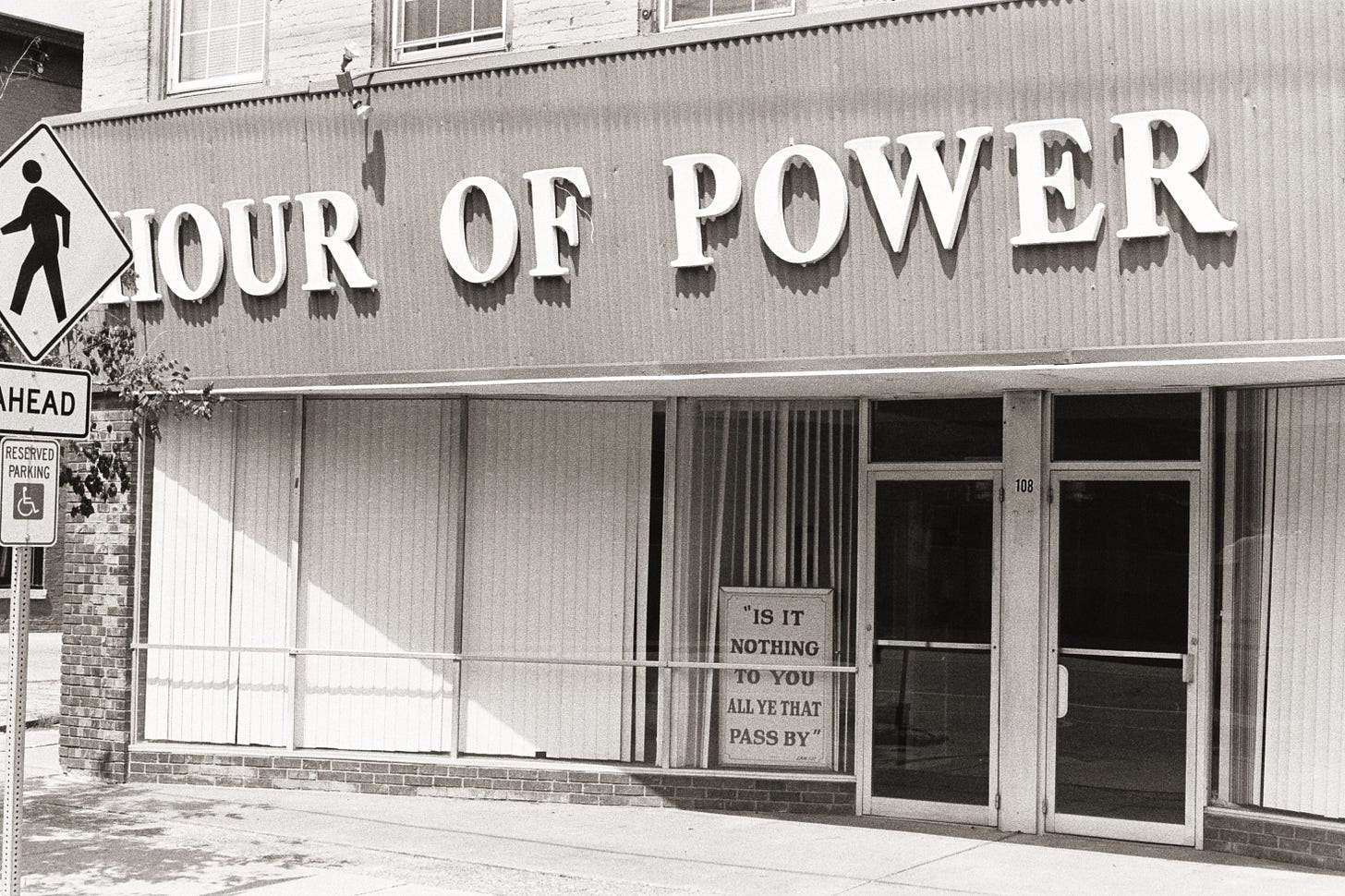

Back in the car, I drove through the eastern side of Louisville and over one of its curving, straight-ribbed steel bridges into Indiana where the subburbs for a Kentucky city cropped up, bleeding into its own, historic small town. I hit the breaks, hopping out to photograph a street-side church called the “Hour of Power” that had in its windowed front a sign reading something curiously ominous that only the development of a recently purchased roll of film will tell. I drove on.

Coming to another small town amidst the growing chain fast-food, gas station, and discount tobacco-strewn four-lane highway, I saw a log cabin, parked again, hopped out again, and took a few photos of it and another white wooden building across the street clad almost entirely in enamel auto-related signs old and new. I drove on again like this until another photo appeared with plenty of shoulder and little enough traffic to allow a stop—a burgundy Chevy G20 van partially hidden by wilding foliage, a car like the one I’d nearly bought and might have been happier with already grown over at the end of a different life belonging to some other person or some other universe.

Corn fields returned to the landscape, and I realized I was back on the Ohio River Scenic Byway—still no river visible but far more scenic than before.

I found the O’Bannon Woods State Park, paid the $9 non-resident entry fee, continued to the campground entrance booth where an elderly woman—large in the way someone who was never too large might become in old age—with silver-grey mid-length hair took my name. From her, I bought a bundle of firewood and a bag of ice, and she gave me the wrong change, making it an overall gain for me. I was only somewhat certain what I’d handed her; still, I took the gift without a word, knowing I’d need the help to avoid breaking budget.

My campsite was being used by two small girls on scooters who, I guessed, had also done the chalk drawings at its front. Their parents hollering caution, I made sure to park towards the back of the lot to leave their drawings exposed and bid hello to my new neighbors. But wanting the river, and with the map revealing the impossibility of walking to it from the campground’s loop, I didn’t stay parked long. On the way out, I stopped to ask the silver-haired woman how best to get to a good spot to swim.

“Well, there’s the Blue River…”—she didn’t offer another option—“and so you go back out to 62, take a left, and go about a mile, there’s a log and you can park across the road.” I repeated her directions and she assured me I wouldn’t miss the fallen tree.

I saw the log before growing at all pessimistic. Having endured Kentucky’s closed-off beauty and surprisingly brown, unreachable rivers, I was ready to be disappointed by the same in Indiana and delighted to be so quickly proven wrong.

A convenient spot to park appeared. Taking it, I walked across and down the path both marked and disguised by the log—whether it was “the” log or simply one of many of equal utility to such a purpose, only the silver-haired woman would know, and perhaps not even she would be certain.

Resplendently, the roadside strip of shaded wood broke open into green and gold, as if the highway’s deep-yellow, sun-caught stripes had suddenly effervesced into the million glinting tree leaves and blinding grass blades tufting the river’s edge. Fucking Thomas Kincaid.

Peaceful and covered in lush nooks, the river’s bottom was all smooth stone, each one fit for skipping, and none slicked over with moss or algae. There was a small summer rapid to the right where the banks hemmed closer, forcing a gentle cut into the river-bottom where a tree had fallen. Half of it had been cut off, and it was occasionally proving itself an advanced obstacle for the casual kayak renters coming down the natural sluice.

The water spoke the river’s name. Blue like the eyes of someone you can’t forget; and in places, golden-brown ringlets dressing a deep-churning green, and deeper where stared upon. But this only a trick of sun and shadow, for once in it, the water became clear enough to see one’s feet standing at its lowest points.

I changed into canary yellow trunks and left my shoes, shirt and jean shorts at the trail’s edge and waded with my backpack to a corner of the island adjacent to rushing little rapid and brilliant with white and cream-colored stone.

Soon enough, a group on horseback approached from the opposite bank, pausing to regroup and ford, some of them whooping with Western joy. They were on mules. Another, smaller group came later, and then three more of kayakers, the leader of each one all attempting the rapid at its deepest and deceptively easiest portion only to surge uncontrollably towards remaining trunk of the half-cut log and capsizing, losing whatever they’d brought along with them.

I rescued the hat of one such imprudent kayaker and pulled out a Michelob Ultra bottle, now half-filled with river water, for another to whom I remarked, “you did better than the last guy.”

After so many lonely days on the road, and in spite of the embarrassment of my counterparts, I was glad for the brief but frequent company—the resident troll of the Little Blue, collecting payment in small denominations of self-consciousness.

I was tempted to speak to one of the rapid’s ill-goers who’d seen a snake and lost his paddle, but I noticed that he was only smiling through an otherwise thorough humiliation; he could tolerate, even enjoy, the laughter of his friends, but not a less-than-perfectly-charismatic jest from a overly familiar stranger. I stayed silent, listening to them offer beers and set off again before opening Summer and Smoke to read the set recommendations.

Least-Heat Moon writes, “You never feel better than when you start feeling good after you’ve been feeling bad.” The river renewed the truth of this to me, as all good stretches of good rivers will do.

I read while the sunscreen hardened against my skin and plunged into the tossing deepness of the rapid to swim against its current as long as I could before turning to float down its length on my back, rolling back over to swim and then back over to float again and again down the hundred yard stretch that hugged my private isle of rock and sun.

At one interval, I laid down and smoked a cigarette, doing nothing more, and in this longest moment, a great sense of synchronicity descended upon me, soaking into my being meat and bone. This would be a good year, one that goes my way, and my way was, conveniently, the highway. And few better than this one, 62, following the Blue River.

Back at camp, I settled in: organized all my small things, folded recent receipts into the envelop stowed in the glove box, removed the day’s accumulated trash, put the solar battery on to charge along with the lamp, and turned the picnic table next to the fire pit into a kitchen. When I was finally ready to get my bag of ice, I found all three of the freezers locked. So be it. It was only just warm; I could sleep through the night without cold water to cool me.

I walked in my towel to the camp’s communal showers. The water was unbearably hot at first, but I was grateful for my first proper shower since West Virginia. I paid particular attention to my toe, which was well on the mend and uninfected, and the several new cuts acquired at the river.

The perfection of the day brewed well into the evening. Pleasantly dry and freshly clothed, I toasted two slices of the bread bought in Ironton and sliced into the tomato now ripe to the point of bursting and deep red like the first sight of blood, sprinkling it with flaky salt and eating the smallest of the slices while others of Spam fried on the cast iron skillet.

Sated and renewed, I lit a fire, boiled water for chamomile tea, and waited for it to cool just enough before lighting a last cigarette.