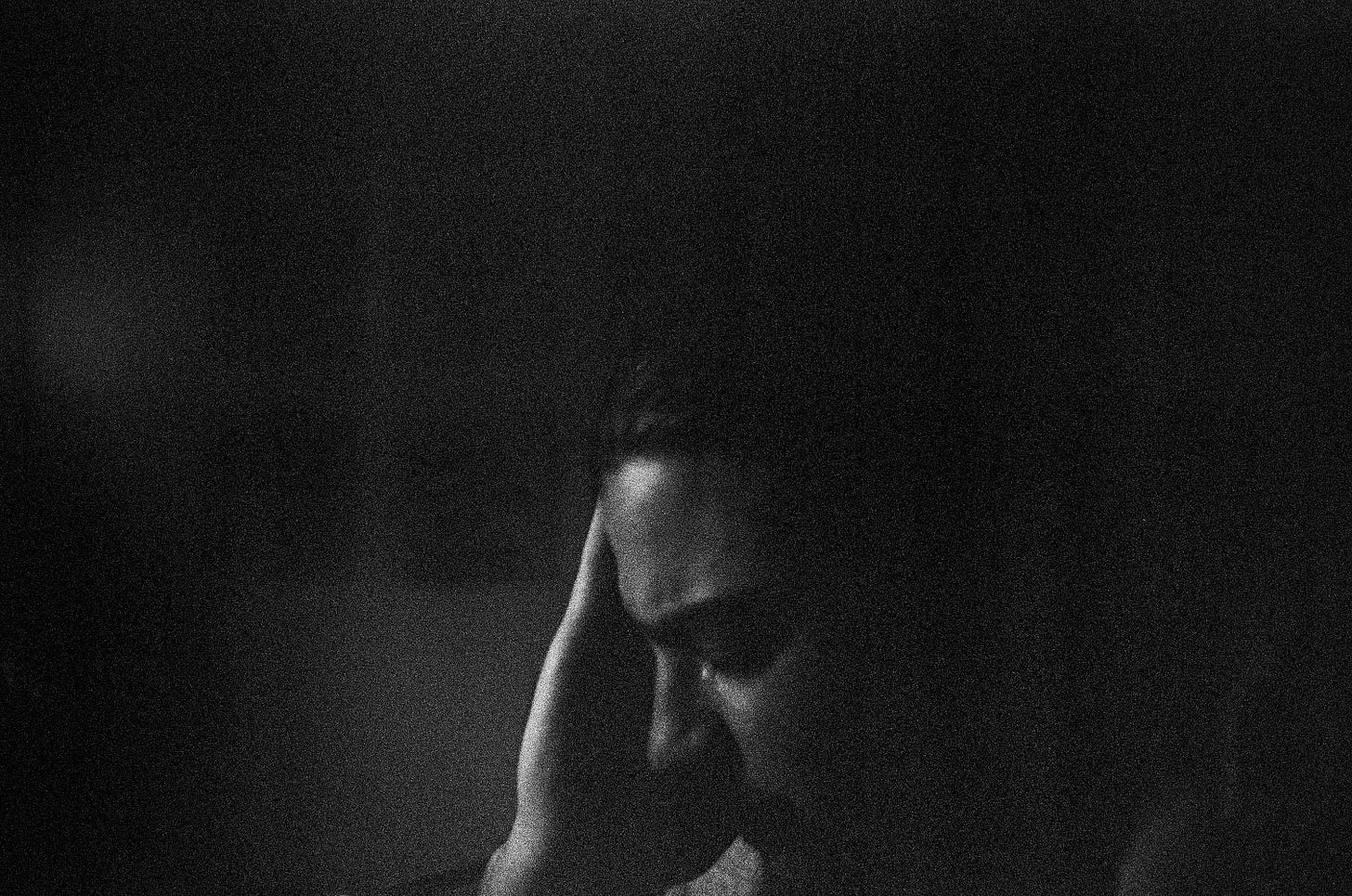

A few weeks ago, it must be at least two, I was prescribed a mood stabilizer. The initial, smaller doses are still sitting lopsided in their unopened containers on the cardboard shoebox lid I use to keep my toiletries upright on the wire shelves in the bedroom corner portion of a studio I’ve been calling home when speaking to my dog and “the studio” when speaking to everyone else I’d rather not know I was living full-time in a room without a full bathroom or a proper kitchen that is technically a commercial space.

I’ve been waiting to start the lamotrigine until I can prove whether or not the mental disorder I believe myself to be experiencing — “believe” because solid diagnoses are the privilege only of those with greater resources of time, money and insurance — is something I can conquer on my own. Theo criteria for beating it would be if I could somehow make it to the gym down the street for three lifting sessions inside of a week. But two weeks have gone by with a third beginning, and I don’t feel any more motivation coming on to accomplish the feat. It’s more complicated than that, becomes more complicated the closer I get. New things get added—finishing or starting a new sculpture, spending time on a song, practicing singing, taking photos, doing yoga, editing my Instagram feed, meditating, grocery shopping, taking the dog for a walk, running, writing if I can. To-do lists used to be the way I stayed productive; now, they are the way I remain chained to the floor.

I don’t think I want it all, to be a writer, a sculptor, photographer, singer, songwriter, but my mental disorder does. So far, the symptoms I experience most prominently feature under the categories of Bipolar II and Borderline Personality Disorder, though not excluding ADHD and some others, in the DSM V. Once I learned what it was, past hypomanic episodes became suddenly and identifiably stark, especially after the combined effect of cannabis and Wellbutrin in May conjured an episode of full-on mania complete with signs of psychosis, albeit mild, in which I was certain god himself was acting directly on my body by invoking an intensely physical anxiety response. Perhaps, in retrospect, the psychosis wasn’t all that mild.

I’d had a glimpse of mania once before, ten months prior, which resulted nearly in my lunatic wandering the streets of Brooklyn and definitely in my regrettable and premature departure from what had been, for many reasons mostly personal, an incredibly stressful but otherwise dream job for County Highway. It was the last time I felt a sense of singularity, of synchronicity of the creative and professional, and my mind couldn’t stay healthy under the pressure.

The job offer had come both unexpectedly and conveniently, following the conclusion of my extended practice of The Artist’s Way. Having felt the need for an extra month of an already three-month program of morning journaling and emotion-ringing exercises that tenderly yet painfully massaged my inner child, I added a fourth and then a fifth month; I wanted to be certain of the self-liberation. When I got the call with the surprise offer, I accepted it immediately, knowing that God—or at least Good Orderly Direction, as Julia Cameron puts, and I still take, it—was rewarding me for the tearful efforts made in the previous months. How could it be otherwise?

Issues arose in my relationship, for both having accepted an offer so readily without discussion and the duration of absence it would require. These took their time to process—trust was lost and had to be regained—but they worked their bitter magic in the meantime, exacerbating the pressure of the job itself. But when both came to a head on a late summer morning on a Friday in Brooklyn, I did not realize then that the rapid narrowing of my visual field, the blurring of its peripheries, the sharp increase and scattering of my heartbeat, and the ethereal and fearful wooziness around my ears were signs of the sort of panic attack that would later mark my manic and hypomanic episodes.

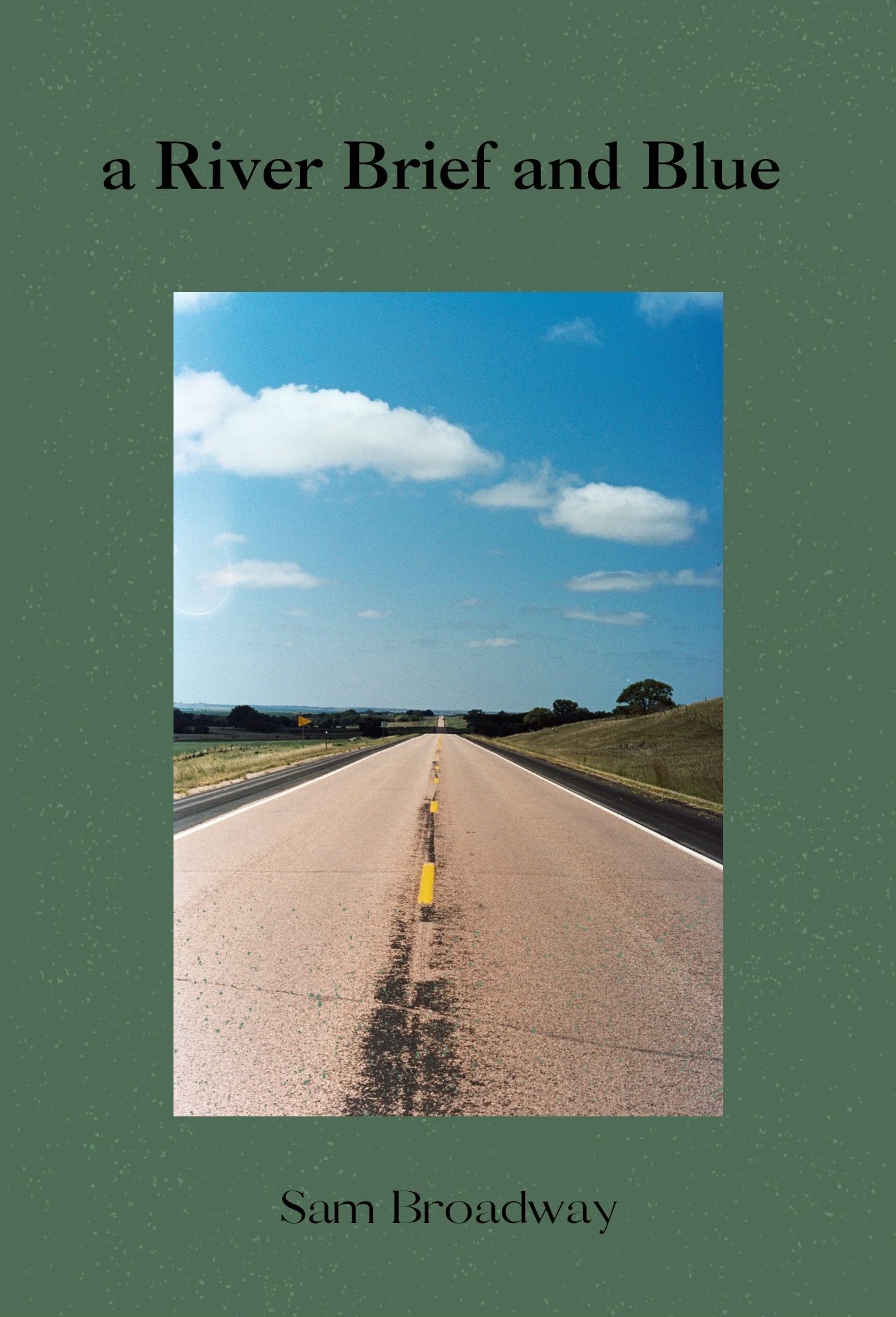

To me, then, the feeling was only god. And I took his word, heard in my body as it seemed, to mean everything had gotten to be too much. I simplified; perhaps in the wrong way, but I simplified. I decided to quit County Highway—a decision the grief of which matured into a major depressive episode only two months later, and the regret of which I still encounter from time to time a year later—and the next day, I packed the car and started driving, for the first time in a week, West instead of the originally intended North.

I had already begun telling people, as if it were a biblical parable, about my quixotic inability to drive in the direction of Connecticut: the battery dying a few days earlier had been an act good and orderly albeit distressing in its pre-interpretation. And as my delusions grew grander and grander as I made the long exit through the tunnel and out of the city—I wouldn’t tell them I was quitting, I’d just disappear, to punish them for their lack of consideration, and to create a manhunt of unparalleled marketing and self-promotional consequence—I looked for more signs that might serve the justifications my unwell brain had already decided upon. I bought a scratch off at a gas station in Jersey City, and when I took it in to redeem my $20 reward, I was dumbfounded that it wasn’t actually a winner—I’d misread or misunderstood the terms—and left feeling cheated, another reason to get as far away from the job as possible.

And I did find them, fresh signs, and wrote about them as often as they appeared. I didn’t get home to my girlfriend any quicker; instead, I took the slow road, convinced not only that I had cut out the worst components of the job—the social media posts, the interviews, the work—in favor of preserving and reinvigorating its best parts—the pace, the introspection—but that I was also now writing a book sure to be considered the next Blue Highways. I was the man who couldn’t make things go right but could at least go. People I met and told about my project were encouraging, even exhibiting the sparkle of admiration in their eyes as I told them. Months later, after I’d recovered enough from the depression that entire ordeal eventually engendered to sufficiently digest the fear of rejection, I pitched the book. I know, now, that I’ll never finish it, that what I set out to right has since become the wrong thing entirely.

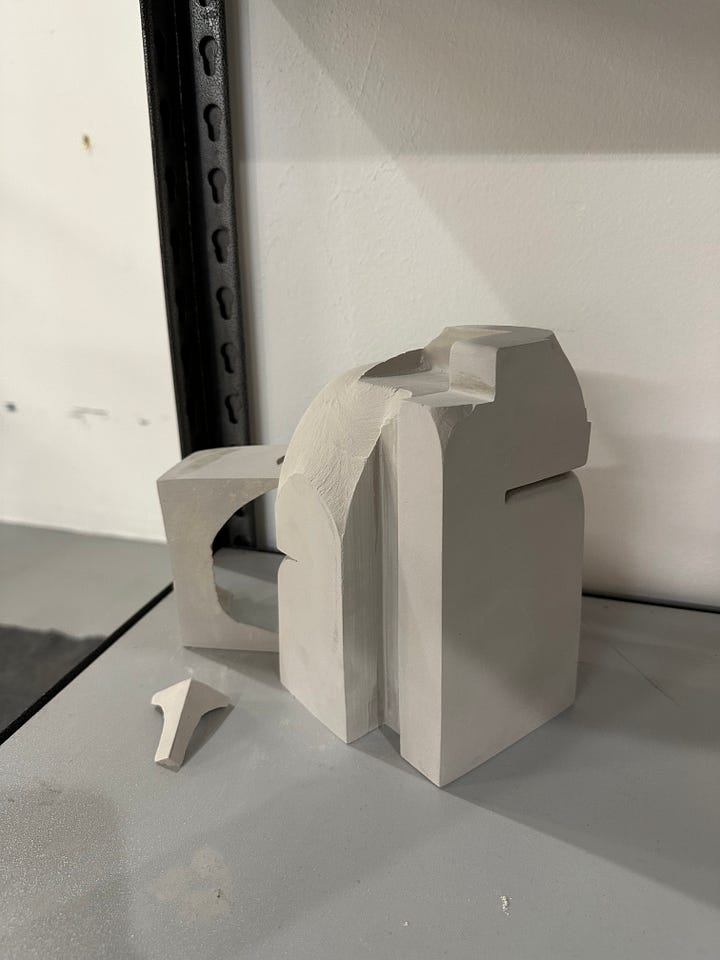

That brief blessing of synchronicity gone, destroyed or used up or blasphemed or disregarded, I tried my hand at new things. If I wasn’t writer and heir to William Least Heat Moon, then perhaps another of my talents, known or unknown, would lead the way. I wrote a few songs, finished fewer, played with clay, which lead to dreaming up a design company, but completed fewer prototypes than I had ideas for. At one point, I became certain I only had to figure out how to make enough disco-tiles hotdogs to efficiently keep up with demand. By the end of that episode, I’d only made seven or eight; all but two were given as gifts.

The problem with hypomania isn’t that the frenetic energy eventually stops—being considerably healthier and more palatable than pure mania, the continuance would be welcome—it is that the delusion takes far longer to die out. Before it can, before a truer purpose and a more sound, realistic and responsible vision can emerge, the mania’s converse has first to set in. And it does so by feasting on the always already impossibility of the unmet expectations of the previous mode. Delusions rot to feed the maggots of major depression. My energy declined, my designs failed to materialize, the company withered along with them, my effort suffered further from a reality sinking into the fetid waters of self-doubt and disbelief.

There was likely nothing wrong with the ideas themselves, just as there was nothing inherently erroneous with premise of the book I’d started months before nor the songs begun in the weeks prior; the fault lay with the container, in my own inability to maintain sufficient adherence to the ideas or the plan that would see them executed. The mind, my mind, simply shifts too frequently to resist the vicissitudes of inspiration and the whims of each new alluring fantasy. And with each shift, a new identity and an accompanying crisis therein.

Now, at thirty-four, I cower at even the faintest whisper of intuition to act on a creative notion. If grander solutions led nowhere but to the lonely shell that previously blazed with their fury, then what could small efforts afford? I have so often sought advice on various projects that the repetition sewed my own shunning. Encouragement for the manic-depressive is chronically deficient, and the sufferer perpetually imagines what might have occurred had there been just a little more, while the owner of its source knows there is nothing else to give to make the difference. The irony is that, seeing a past littered with half-wrought efforts and outright failures, and without the temperance of the community to which he once had access but from which he has grown increasingly alienated, the manic-depressive makes ever grander and riskier attempts to slingshot his way into a secure position. He may, like me, consider streamlining the production of a line of luxury pop-art decor items or ideate an entirely new artistic process beginning with sculpture and ending with photo-realistic woodblock prints. With each new interest, a new and vibrant career materializes from the accumulated pixelation of all this new “flight of idea, which despite feeling can be found verbatim in the DSM. With this, how to present the new persona becomes a problem with its own set of complications each demanding a response.

Self-presentation, self-representation, particularly across an aestheticized digital plane, which some called “branding” but which others like myself experience as a form of self-lobotomization—like cramming the guts of all one’s consciousness-oozing personality through a industrial exhaust fan, hoping most or all of it will splat across a standard sized sheet of printer paper twenty feet away—becomes necessary to complete the transition to the new “you” and buck the setting-in of self-aware delusion. (This is a far easier task for company that has never experienced thought, but for an individual it is entirely impossible comprehensively; and yet those who do use the term “branding” for the personal version of this exercise seem to experience so little thought that they are able to express contentment with, even gratitude towards, the resulting set of images. For myself, who has been so many selves — even within this own piece, or were you not watching for tonal shifts — it remains just as impossible but primarily because of the disparate strategies employed and the eventual disgust by which the next self regards the effort of the previous.)

At some point, there will be a time to move on, to find a new community where the manic-depressive has yet to feel unwelcome and where he has no known history of faking it within which he can reconstitute an identity, a trick I myself have executed to the rhythm of every nearly two and a half years. Lacking the power of follow through, and given the nature of encouragement—that it is always, for such a person, untimely—sling-shooting into a new hierarchy and fresh social context as only a strange drifter can becomes the best antidote to languishing in greying pastures.

The point of this wasn’t to seem an expert on psychological disorders and their symptoms, nor was it to make generalizations with such solipsistic examples. I suppose the purpose, admittedly in contradiction of what I earlier stated, was simply to act upon my intuition and in hopes that doing so would reveal a deeper and longer-running creative impulse. In lieu of an as-yet unidentified means by which to accumulate recognition and more crucially money in exchange for the access to the various changes in my identity and the limited resulting examples of the work they produce and thus embrace them in their entirety, I’ve chosen to gloss them in the only way I know how over the course of a disjointed afternoon and evening between baser obligations.

Perhaps I will always be a writer because I always have been; though I find the self-as-never-ending-subject—the self to such a consistency-troubled individual is the most frequently recurring theme—to be perfectly distasteful. Still, in admitting I’ve made a poor sculptor, among so many other things, I can say without feeling overly boastful, that I do have a gift with words, for molding them into their most proper order, for remodeling cliché into the previously unexplored. I may not be the next Franz Gertsch—as I have recently imagined—but I may be, at least in the more or less accidental sense, developing a practice in spite of my deliberate efforts. Something may emerge, the arc of which bends from too low and for too long to ever be visible.

With that in mind, I’m taking my hands off the wheel and inviting Cameron’s G-O-D to do the steering. After all, I have a great deal of work already done that I might as well share, and which being very unlikely to ever turn into the book I lunatically envisioned, may at the very least further reveal to me the writer than I truly am.

Beautiful